Woodrow Wilson, Président des Etats – Unis d’Amérique et Le Marquis de Lafayette, Picpus, 1918

Par Yorick de Guichen, 4 Juillet 2022

Cliquez ici pour la version PDF en français.

Cliquez ici pour la version PDF en anglais.

VERSION FR

Chaque année, la Société des Cincinnati invite un étudiant boursier américain à séjourner en France pour commémorer et faire perdurer le lien d’amitié qui unit les Officiers français et américains ayant combattu pour la guerre d’Indépendance des États-Unis. En Juillet 2021, John P.P. Beall sort à peine de l’avion, et je lui demande : « sais-tu faire du vélo ? ».

Ses valises posées, nous partons à la découverte de différentes statues : Washington et Lafayette – place des États-Unis, George Washington – place Iéna, Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette – en face du Grand Palais, Amiral de Grasse et ses troupes – sous le Trocadéro, Statue de la Liberté – quais de Seine, plaque commémorative de la signature du Traité de Paix reconnaissant l’lndépendance des Etats-Unis – ancien hôtel d’York rue Jacob, et enfin rue du Cherche Midi : l’hôtel particulier du Maréchal de Rochambeau (premier siège de la Société des Cincinnati de France). Il est 16 heures, John et moi déjeunons dans le quartier de Saint Germain des Prés. Soudain je lui propose :« et Picpus ? ». John me répond « why not ? ». Nous fonçons sur nos bicyclettes à travers Paris, pensant arriver trop tard au Cimetière de Picpus (proche de la place de la Nation).

Une femme au regard d’eau nous ouvre un grand portail bleu. Geneviève nous rassure : « nous fermons dans une heure ». Nous visitons la Chapelle – en prière perpétuelle depuis la fin de la Révolution française – et sommes petit à petit pris par l’intensité et le recueillement qu’impose le lieu. Derrière ce grand portail bleu, le temps s’arrête à Picpus.

John et moi allons nous recueillir sur la tombe de Lafayette. Pendant notre minute de silence, je remarque une gerbe en métal juste derrière sa tombe. Il m’est difficile de la distinguer, sa partie haute semble manquante. J’hésite un instant et suggère de la redresser. J’ouvre cette petite barrière qui nous sépare, je longe le tombeau et constate qu’une partie de cette gerbe s’est brisée, et que l’ensemble est dessoudé de son trépied. Je regarde John et lui glisse en souriant : « We have a mission now ».

6 mois passent. Nous sommes au mois d’avril, je suis de retour d’une exposition MEANING – Honoring U.S. engagement in WWI – au Collège Pierre Norange à Saint Nazaire avec une classe d’élèves de 16 ans en section Défense. La crise en Ukraine vient d’éclater et j’y fais un discours sur la paix devant Madame la Consule des Etats-Unis Elizabeth Webster qui ouvre la conférence. Le lendemain, arrivant tôt à Paris, je décide de repasser par Picpus. Le jour se lève à peine, le cimetière est fermé, mais le grand portail bleu est entre-ouvert. Je rentre. Sur ma droite un chien aboie mais je poursuis mon chemin. Je passe la Chapelle, traverse les allées des jardins jusqu’à arriver à l’enceinte du cimetière. Sa porte aussi est ouverte. J’y retrouve la tombe de Lafayette et derrière celle-ci la gerbe git toujours là, brisée. Je regarde alors le tombeau. Et je lui pose la question. « Que veux-tu que je fasse ? ».

Je décide de rebrousser chemin. Dans les allées des jardins, je rencontre le Conservateur de Picpus qui m’attend avec son chien.

- « Le cimetière est fermé » me dit-il.

- « Oui, mais la porte était ouverte ? »

- « Que faites-vous ici ? »

- « Je viens me recueillir sur la tombe de Lafayette. Et je crois qu’une plaque y est fêlée. »

- « Il n’y a pas de plaque fêlée » me répond-il.

- « Vous en êtes sûr ? Allons voir ensemble car j’ai un doute. »

- « Ah, mon ami, ce n’est pas une plaque, c’est une couronne, c’est très différent ! » me dit-il (il insiste sur le « très »).

Nous convenons ensemble de réparer cette couronne. Son nom est Jean-Jacques Faugeron, il se charge de contacter les services techniques du Gouverneur Militaire de Paris, équipe compétente pour cette restauration.

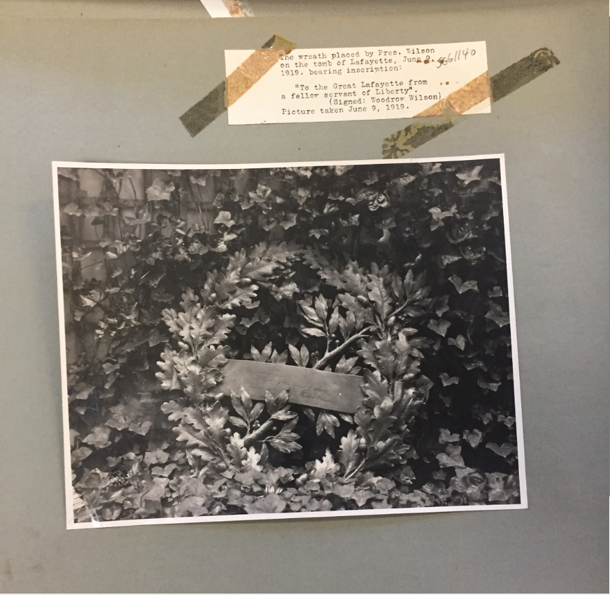

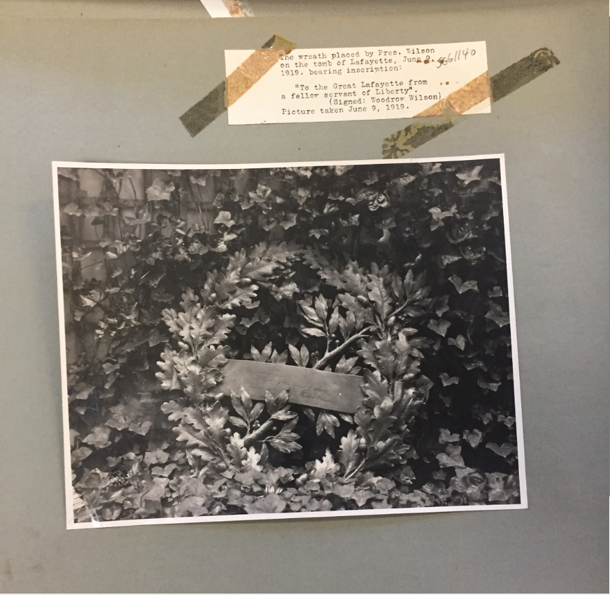

Sur cette couronne de métal est inscrit, en lettres manuscrites : « To the Great Lafayette, from a fellow Servant of Liberty, Woodrow Wilson, December 1918 ».

En voici maintenant l’histoire :

L’Armistice de la première guerre mondiale vient d’être signée le 11 novembre 1918 à 5:10 du matin, heure de Paris. Les combats s’arrêtent à 11 heures. La paix est encore fragile, les océans peu sûrs. Après un voyage de 9 jours en Atlantique encadré d’un convoi de 42 bâtiments, le Président Woodrow Wilson et sa délégation arrivent à Brest le 13 décembre 1918. Wilson vient régler la Paix des Nations, gérer la question délicate des frontières territoriales et trouver un accord sur les « réparations » à infliger aux vaincus.Woodrow Wilson est le premier Président des États-Unis en fonction à fouler le sol français. « Je suis accueilli avec tant de joie que j’ai l’impression d’être à la maison » écrit-il dans son journal. Ce dimanche 15 décembre 1918, il se rend avec son épouse Edith à l’office de l’Église Presbytérienne Américaine, rue de Berri, puis ils traversent Paris en automobile. Personne n’attend Wilson à Picpus. Accompagné du Brigadier General Harts, d’un agent des Services secrets et d’un officier français, Wilson va se recueillir sur la tombe du Marquis de Lafayette.

Dans une lettre adressée à sa famille datée du 15 décembre, Edith Wilson écrit : “Ce matin, nous nous sommes rendus à l’autre Église américaine, et juste après, sur la tombe de Lafayette pour y poser dessus une gerbe ou, comme ils l’appellent ici, une “couronne”. (…) Le cimetière se situe sur le terrain d’un ancien couvent où résident toujours de vieilles nonnes, toutes de très vieilles femmes habillées de capes blanches et de drôles de chapeaux blancs de cette forme, et sur leurs torses deux cœurs saignant avec des langues de feu. Nous avons conduit le long d’une longue allée d’arbres (…) jusqu’à un coin calme où se trouvent seulement quelques tombes de vieilles, vieilles familles de France. Lire les inscriptions des noms qui y figurent est comme tourner une page de l’histoire.”

Jour de l’Indépendance américaine, 4 Juillet 1917.

Le journal Saint Louis Post Dispatch décrit : « Complètement non annoncé, le Président conduit vers le vieux cimetière de Picpus. Quand il apprend qui l’appelle, le vieux portier est tellement stupéfié qu’il n’arrive pas à ouvrir le portail ». Le Docteur Cary T. Grayson décrit dans son journal : « le Président retire son chapeau, entre sur la tombe de Lafayette et y dépose une couronne naturelle composée de feuillages de chêne et de branches de lauriers. Au centre il y place sa carte de visite personnelle, au verso y est écrit de sa main : « In memory of the Great Lafayette, from a fellow Servant of Liberty, Woodrow Wilson. December 1918. » Grayson ajoute : « Au moment où le Président a déposé la gerbe sur la tombe, il a baissé la tête et est resté en silence devant l’endroit où repose le fameux Français qui avait aidé au combat de l’Amérique pour la Liberté ». Le journal Saint Louis Post Dispatch ajoute : « La nouvelle de la présence de Wilson se répand rapidement au sein du couvent de Picpus. En partant, il passe devant une ligne de nonnes âgées, toutes sorties lui rendre hommage ».

Le voyage de Wilson en France se poursuit, il part en Angleterre pour revenir ensuite à Paris où il prononce un discours à la Chambre des Députés au Palais Bourbon. Dans ses statuts, l’Assemblée n’a pas prévu de recevoir un Président étranger à sa tribune. Qu’importe, elle contourne la règle et décide de siéger « debout » !

« Comme toute l’assistance, le président du Conseil, M. Clemenceau, le président de la République, M. Poincaré, et le président du Sénat, M. Antonin Dubost, sont debout devant leurs fauteuils, disposés face à la tribune. Seul est assis au premier plan l’interprète M. Mantoux, prenant les notes sténographiques qui lui permettront de traduire le discours de M. Wilson. »

President Wilson giving a speech at the tribune of the House of Representatives in the Palais Bourbon © Assemblée nationale _ L’Illustration n° 3962 February 8, 1919. « Like all the assistance, the President of the Conseil, Mr. Clemenceau, the President of the French Republic, Mr. Poincaré, and the President of the Senate, Mr. Antonin Dubost, all are standing up in front of their chairs, facing the tribune. On the first row, Mr. Mantoux is the only man sitting. His duty is to take notes and translate President Wilson’s speech.»

Pendant son séjour, Wilson a probablement cherché un artiste français pour réaliser sa création, une couronne identique à celle qu’il a déposée, non plus éphémère mais permanente. C’est au sculpteur renommé Auguste Seysses qu’il passe commande pour en réaliser l’exacte réplique, en bronze cette fois-ci. SEYSSES signe l’œuvre en lettres capitales en bas à gauche sur l’un des branchages.

6 mois ont passé depuis la première visite de Wilson à Picpus, on imagine tant son impatience est grande à espérer que l’exécution de sa création soit en parfaite adéquation avec son intention d’origine. Dans son carnet, Ray Stannard Baker, secrétaire particulier de Wilson, relate que ce samedi 7 juin 1919 dans la soirée, le Président s’enquiert auprès de lui de la livraison de l’œuvre qu’il attend. Tard le lendemain matin, le dimanche 8 Juin 1919, Wilson retourne une seconde fois à Picpus, seul, y déposer la couronne de bronze. Le Docteur Cary T. Grayson commente : « cette couronne (…) est une superbe création. Sur le dessus est attachée une carte permanente en métal sur laquelle sont manuscrits les sentiments du Président. » Sur feuille d’or, l’écriture de Wilson y est scrupuleusement reproduite à l’identique : la même profondeur du trait, le même rythme : « To the Great Lafayette, from a fellow Servant of Liberty”, signé des 13 lettres de son nom : “Woodrow Wilson”. Chaque mot y a son importance, chaque lettre capitale également. Même la date d’origine est respectée : « December 1918 ».

Dans son carnet, Grayson décrit la scène: « le Président est entré sur la tombe et y a déposé cette couronne de ses propres mains. Il s’est replacé en arrière, l’a regardée, l’a ajustée jusqu’à ce que la couronne trouve la place qui le satisfaisait » (…) Il ajoute : « Tous ceux qui l’ont vue ont apprécié le sentiment derrière ce geste (…) Pour le peuple français, cette couronne rappelle(ra) par son caractère permanent la première visite d’un Président américain en France (…). Cette couronne attira l’attention de tous » conclut-il. « Et cela m’a couté une petite fortune » lui confiera plus tard Wilson. Tout porte à croire que ce geste émane d’une intention personnelle de Woodrow Wilson, qu’il tient à déposer sa création de ses propres mains et dans la plus grande discrétion. Aucun discours, aucune photographie officielle. Si ce n’est celle-ci, retrouvée dans son album personnel, et datée du lendemain.

Au milieu du cimetière de Picpus, lieu chargé d’histoire, meurtri par la Révolution, sur la tombe du Marquis de Lafayette, Major General de l’Armée des États-Unis, considéré comme le fils adoptif de George Washington, héros des deux mondes et dont le corps repose recouvert de la terre provenant de Mount Vernon, Woodrow Wilson, premier Président américain à traverser l’Atlantique, signe de sa main l’un des plus beaux hommages que l’Amérique puisse rendre à la France, à un moment décisif de notre histoire. Il s’y présente humblement, en compagnon Serviteur de la Liberté, face à celui à qui sa nation doit tant. Après un conflit fratricide, le champ de bataille le plus meurtrier de l’histoire de l’humanité, alors que la paix n’est pas encore signée et que tout arbitrage fait l’objet d’âpres négociations entre vainqueurs et vaincus, Wilson porte à l’Europe le projet qui lui est le plus cher : une Société des Nations pour une paix durable.

A quoi Woodrow Wilson pense t’il en se recueillant devant la tombe de Lafayette ? Wilson attend cette rencontre depuis fort longtemps et s’y est naturellement préparé. En tant qu’américain et homme d’état, il est sûrement habité par ce doux bonheur de se retrouver « avec son plus ancien Allié » ayant combattu ensemble pour cette « cause commune » si chère à son prédécesseur George Washington. Mais aussi est-il habité par ce projet, aussi immense que novateur, de diffuser les idéaux démocratiques en Europe. Enfin doit-il gérer l’enjeu capital – et dont il endosse la responsabilité : « apporter ordre et organisation à la paix pour son pays et pour tous les peuples du monde ».

L’audace, l’idéal, le courage, le sens du gouvernement des hommes, la vision, la foi aussi, tout rapproche ces deux figures que presqu’un siècle sépare. Et autour d’eux, sous leurs pieds, des milliers d’âmes écoutent ce que se disent en silence deux géants de l’Histoire.

Yorick de GUICHEN

Société des Cincinnati de France

Membre du Conseil d’Administration

« Pour la Société des Cincinnati de France, redonner tout son éclat à la couronne offerte par Wilson, c’est rendre hommage à un symbole oublié de l’histoire de l’amitié franco-américaine. C’est aussi rappeler que les valeurs qui nous unissent sont profondément sincères, actives, et traversent le temps. »

Loÿs de Colbert

Président des Cincinnati de France

« L’amitié s’entretient : la restauration de cette couronne contre les outrages du temps est un devoir. Celle-ci témoigne de la vivacité du lien transatlantique entre la France et les États-Unis d’Amérique. Je remercie la société des Cincinnati de France pour la préservation de la mémoire face à l’oubli ».

Général Christophe ABAD

Gouverneur Militaire de Paris

La Société des Cincinnati a pour vocation de perpétuer le souvenir de fraternité d’armes qui unit Officiers français et américains ayant combattu ensemble pour l’Indépendance des États-Unis d’Amérique. Fondée en 1783, son premier Président fut George Washington. Hier comme aujourd’hui, les Cincinnati s’attachent à célébrer les valeurs de liberté, d’initiative, de dévouement au bien commun, et entretiennent les liens d’amitiés qui unissent nos deux pays depuis plus de deux siècles.

VERSION ANGLAISE

What two giants of history say to each other in silence

Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States of America and the Marquis de Lafayette, Picpus, 1918

Yorick de Guichen, July 4th 2022

Every year, the Society of the Cincinnati invites one American student to France to commemorate the friendship between French and American officers who fought together during the American War of Independence.

On July 2021, as soon as John P.P. Beall gets out the plane, I ask him, “Do you like biking?”

After dropping his luggage, we leave home to discover different statues: Washington and Lafayette – place des États-Unis; George Washington – place d’Iéna; Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette – in front of the Grand Palais, Admiral de Grasse and his troops – under the Trocadero. We also ride along the quays of the Seine to the Statue of Liberty, then on rue Jacob to the Hotel d’York to see the commemorative plaque of the Peace Treaty recognizing the Independence of the United States, and then rue du Cherche Midi to the Maréchal de Rochambeau’s mansion, first headquarters of the Société des Cincinnati de France. It is around four o’clock in the afternoon, John and I have lunch in Saint Germain des Prés. Suddenly, I ask him, “And Picpus?” John answers, “Why not?” We speed on our bicycles, thinking we’ll be too late to reach Picpus Cemetery (close to the Place de la Nation) before it closes.

A woman with eyes the color of water opens a large blue gate. Her name is Genevieve, she kindly reassures us that we still have an hour. We visit the Chapel (where there were continual prayers since the French Revolution until recent times) and we are slowly overcome by the unique intensity and memories elicited by this revered place. Behind the blue gate, time stands still at Picpus.

John and I walk to the tomb of Lafayette. During our minute of silence, I notice a metal wreath behind the tomb, one part of which seems to be missing. I hesitate for one moment, then I suggest that I should put it back in place. I open a fence and notice that one part of the wreath is broken, and the rest is detached from its stand. I look at John and tell him smiling, “We now have a mission.”

Six months pass. It is the beginning of April, and I am back from an exhibition of MEANING – Honoring U.S. engagement in WWI – at Pierre Norange School in Saint Nazaire with a class of students from the Defense section. The crisis in Ukraine has just started and I am making a speech there about peace, in front of the U.S. Consul Elizabeth Webster who opened the conference. The next morning, I arrive early in Paris and decide to return to Picpus. The sun is just rising, the cemetery is closed, but the blue gate is half open. I enter. On my right, I hear a dog barking, but I continue, pass the Chapel, cross the gardens until I arrive at the wall surrounding the cemetery. To my surprise, the door is opened inviting me inside. I recognize the tomb of Layette and behind it there still is a broken wreath. I look at the tomb and ask him, “What do you want me to do?”

I decide to go back. In the alley leading to the garden, I meet the curator of Picpus who is holding on to his dog.

“The cemetery is closed,” he says.

“Yes, but the door was open,” I reply.

“What are you doing here?”

“I am coming to meditate on Lafayette’s tomb,” I reply. “And I think there is a metal plaque that is broken.”

“There is no broken metal plaque,” he responds.

“Are you sure? Why don’t we have a look together?”

“Ah, my friend, that is not a plaque, it is a wreath, that is very different,” he says (and insists on the “very”).

Together, Jean-Jacques Faugeron – the curator – and I agree to have the wreath restored. He says he will manage to contact the technical services of the Military Governor of Paris, an expert team in such restorations. On the metal wreath is inscribed, in a handwritten script: “To the Great Lafayette, from a fellow Servant of Liberty, Woodrow Wilson, December 1918.”

This is the story of the wreath and the plaque:

The Armistice of World War One has just been signed at 5:10 AM, Paris time, on November 11, 1918. Combat ceases at 11 AM.

Peace is fragile and the seas are still uncertain. After a nine day journey across the Atlantic, escorted by a convoy of 42 ships, President Woodrow Wilson and his delegation arrive in Brest on December 13, 1918. Wilson comes to set up the Peace between Nations, to handle the delicate question of territorial frontiers and to find an agreement on war reparations to inflict on the losers. Woodrow Wilson is the first President of the United States of America in office to set foot on the French soil. “I have been welcomed with so much joy that I felt like being at home,” he says. This Sunday December 15, 1918, Wilson attends church with his wife Edith at the American Presbyterian Church, rue de Berri, then they drive through Paris in an automobile. No one expects Wilson to come to Picpus. Accompanied by Brigadier General Harts, a secret service operative and a French officer assigned as a personal aid, Wilson goes to pay his respects to the tomb of the Marquis de Lafayette.

In a letter sent to her family dated December 15, Edith Wilson writes: “This morning we went to the other American church, and afterwards to the tomb of Lafayette to put a wreath or, as they say over here, « a crown » on it.(…) The cemetery is in the grounds of an old convent where there are still some old nuns – all very old women dressed in white with capes and funny old white hoods this shape (…), and on their chests, two bleeding hearts with tongues of fire. We drove down a long avenue of trees (…) to a quiet corner, where are only a few tombs of the old, old families of France – the inscriptions of the names are like turning a page of history. »

Independence Day, July 4, 1917.

Saint Louis Dispatch journal comments: “Entirely unannounced, the President drove to the old Picpus Cemetery, where the amazed gatekeeper was almost too flustered to unlock the gates when he learned who his caller was”.

Doctor Cary T. Grayson writes in his diary: “The President removed his hat, entered the tomb, carrying a large floral wreath composed with oak leaves and laurels which he had arranged for. In the center, he had attached his personal card on the back of which he had written with his own handwriting: “In memory of the Great Lafayette, from a fellow Servant of Liberty, Woodrow Wilson. December 1918.” As the President placed the wreath on the tomb, he bowed his head and stood silent before the resting place of the famous Frenchman who helped America in her fight for Liberty. The Saint Louis Post Dispatch journal adds: “The news of the President’s visit spread rapidly to the convent nearby, and as he left, he passed through lines of aged nuns, who came out to pay their respects to the American chief executive.”

Wilson’s journey in France continues, he goes to England and returns to Paris where he pronounces a speech in the House of the Representatives in the Palais Bourbon. In their statutes, the Assembly has no precedent for receiving a foreign President. Who cares, the assembly will override its rules and sit ‘standing up’!

During his stay, Wilson probably searches for a French artist to realize his vision, an identical wreath to the one he deposited, not only ephemeral but timeless. He orders Auguste Seysses, a famous French Sculptor to create the exact replica, in bronze this time. Seysses signs the masterpiece in capital letters on the left-hand side of one of the branches.

Six months have passed since Wilson last visited Picpus. We imagine how impatient he must be, hoping that his creation and original intention are perfectly reproduced. In his diary, Ray Stannard Baker, the President’s Press Secretary, states that this Sunday June 7, at the end of the day, the President inquires whether the wreath has been delivered. Later the next morning, on Sunday June 8, 1919, Wilson returns a second time to Picpus, alone, to deposit the wreath.

Doctor Cary T. Grayson comments: “This bronze wreath is a superb creation and attached to it is a permanent metal card upon which is written the President’s sentiments.”

Plated with gold, Wilson’s handwriting is perfectly reproduced with the same depth, the same visual rhythm. The text reads: “To the Great Lafayette, from a fellow Servant of Liberty” signed with 13 letters : “Woodrow Wilson”. Each word counts, each capital letter does too. The original date is reproduced : “December 1918”.

In his diary, Grayson describes the scene: “The President went inside of the railing and placed the wreath with his own hands. Stepping back to gaze at it, and then moving forward to change it, until it finally satisfied him.” He adds: “All who saw it were highly delighted with it, and the French especially appreciated the sentiment behind it (…) To the people of France, the wreath will be a permanent memento of the first visit of the President of the United States to France (…). This wreath attracted a great deal of attention. ”It cost me a pretty penny,” added the President.

Every detail reveals that Woodrow Wilson’s intention was to make a deeply personal gesture, that he planned to give his creation in the most discreet manner, by way of his own hands. No speeches were made, no official pictures taken, except this photograph found in his personal diary dated the next day.

At the heart of the cemetery of Picpus, a place filled with history, and so much suffering during the French Revolution, Woodrow Wilson, the first American President to cross the Atlantic stands by Lafayette’s tomb, a Major General of the Army of the United States, considered as the adoptive son of George Washington, hero of the two worlds, whose body is buried under dirt brought from Mount Vernon. The American President signs with his own hand one of the greatest honors America can offer to France, at a crucial time of history. Wilson presents himself with humility, as a companion and “Servant of Liberty”, to the one to whom his country owes so much. After a fratricidal conflict and the most lethal battlefield in the history of humanity, as peace is yet not signed, and as every arbitrage raises harsh negotiations between winners and losers, Wilson brings to Europe a project that he most hopes for: a Society of Nations for a lasting peace.

What was Wilson thinking as he meditated on Lafayette’s grave? He must have waited a long time for this encounter and had surely prepared himself for it. As an American and a statesman, he was undoubtedly filled with a great sense of happiness in meeting with his “oldest Ally”, having both fought for the “common cause”, so priceless to his predecessor George Washington. Also, he is completely focused on his project, as vast as it is new, to spread the ideals of Democracy in Europe. Finally, he must grapple with a crucial issue – for which he accepts full responsibility – : “To bring order and organization to the peace for his country and to the people of the world.”

Audacity, ideals, a government of people, a vision and faith, all unite these two men separated by more than a century. Around them, below their feet, thousands of souls listen to what these two giants of History say to each other, in silence.

Yorick de GUICHEN

Society of the Cincinnati

Member of the Board

« To the Society of the Cincinnati de France, giving all its shine to the wreath offered by President Wilson means honoring a forgotten symbol of the history of French American friendship. It also reminds us that the values that bind us together are profoundly sincere, active, and travel through time».

Loÿs de COLBERT

Societé des Cincinnati de France

President

“Friendship is to be kept up : the restauration of the wreath against the ravages of times is a duty. It illustrates the vivacity of transatlantic ties between France and the United States of America. I am grateful to the Society of the Cincinnati to keep the memory alive “

General Christophe ABAD

Gouverneur Militaire de Paris

The Society of the Cincinnati perpetuates the souvenir of brotherhood in arms which unites French and American Officers who fought side by side for the war of Independence of the United States of America. Founded in 1783, George Washington was its first President. Today as in the past, the Cincinnati celebrate the values of liberty, dedication to the common good, and maintain the friendship that unites our two countries together since more than two centuries.

We would like to thank :

Le Conservateur du Cimetière de Picpus – Jean-Jacques Faugeron et les équipes techniques du Gouverneur Militaire de Paris : Sébastien Mermet et Fréderic Genina.

The Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library Washington D.C., Andrew R. Phillips – Curator & Director of Museum Operations

L’Ambassade des Etats-Unis d’Amérique, Son Excellence Madame Denise Campbell Bauer et Valérie Raphaël-Foussier – Public Diplomacy

La U.S. WWI Centennial Commission, Monique Brouillet Seefried, Ph.D.

Sources :

Photography of the wreath, Woodrow Wilson Scrapbook, ©White House Historical Association.

Mrs. Edith Bowling Wilson‘s Diary, December 15 1918, Library of Congress.

Doctor R. T. Grayson’s Diary – December 15 1918, Woodrow Wilson Library.

Saint Louis Post Dispatch – December 16, 1918, Woodrow Wilson Library.

L’Illustration – n° 3962 – 8 February 1919.

Ray Stannard Baker’s Diary – 7 June 1919, Library of Congress.

The Boston Globe Saturday – Saturday June 7th, 1919 – Woodrow Wilson Library.

Président Wilson, « Nous allons faire un monde pour vous où il fera bon vivre », 3 Février 1919.

G. Lenôtre, Le Jardin de Picpus, Les Pèlerinages de Paris Révolutionnaire, Perrin, 1970.

1919, un Président américain à Paris, Wilson dans l’hémicycle © Assemblée nationale.

Laurent Zecchini, Lafayette, Hérault de la Liberté, Fayard, 2019.

Yorick de Guichen et Hervé Saint Hélier, MEANING_ Honoring US Engagement in WWI, Folowing the Patrouille de France U.S. Tour, Meaning Company, 2017.